At the Columbus Museum of Art (CMA), we believe that play is Serious Business for children. The body of research that supports this belief is deep, wide and filled with good data gathered by folks smarter than me (including Dr. Stuart Brown, The National Institute for Play and Peter Grey). So instead of talking about ‘why’, today I want to talk about what it looks like to foster play and creativity among the adults in a child’s life- particularly in pre-service teachers. At the CMA creativity is what we do. We believe that all of us have the capacity for creativity, no matter what our profession, and that creativity is what we, as humans, need in order to make our worlds more fair, sustainable and beautiful. Children are not just cute ‘pre-humans,’ (much as those of us who are parents may sometimes feel)- they are actually a vibrant and important part of our community and are some of the greatest researchers and practitioners when it comes to play and wonder. If we are to support their learning and amplify their ideas, we need to have teachers and caregivers who have the understanding and skills to support them. An hour-long, imaginative tour at the art museum may be fun and impactful for children, but it’s nowhere near as impactful as the hours, days and months a child spends with teachers, family and other caregivers outside of the museum.

One place we try to support child and adult creativity through play is at Wonder School, a laboratory preschool in partnership with Columbus State Community College (CSCC) and The Childhood League Center. As a lab school, Wonder School includes student-teachers from the CSCC Early Childhood Development and Education practicum program. When asked how many ‘students’ we have, we make it a point to say that we usually have around 20- 12 to 14 “little kids” (preschoolers, ages 3 to 5) and 6 to 8 “big kids” (CSCC students, aged 18 and older) each semester. As a licensed, preschool classroom, we follow Ohio’s Early Learning Development Standards as well as the state mandated assessments. In addition, however, we look for opportunities to highlight and further support what we call CMA’s “Thinking Like an Artist” Skills.

Finding ways to support these skills with children is the easiest part of the job. This is because children naturally “think like artists,” and because most children have not learned to associate “play” with frivolity. At the same time, these skills are most endangered by well-meaning grown-ups who might see them as getting in the way of “real work.” I truly think this shushing is not ill-meant, but comes from teachers and caregivers not knowing the importance of such skills, or how to support them in the classroom. That’s why during orientation with our Wonder School “big kids,” before we even get into general classroom rules and schedules, we start by talking with student teachers about what creativity is, what studio thinking looks like and what role play plays in their own lives. We want to give student teachers the words to describe what they might see.

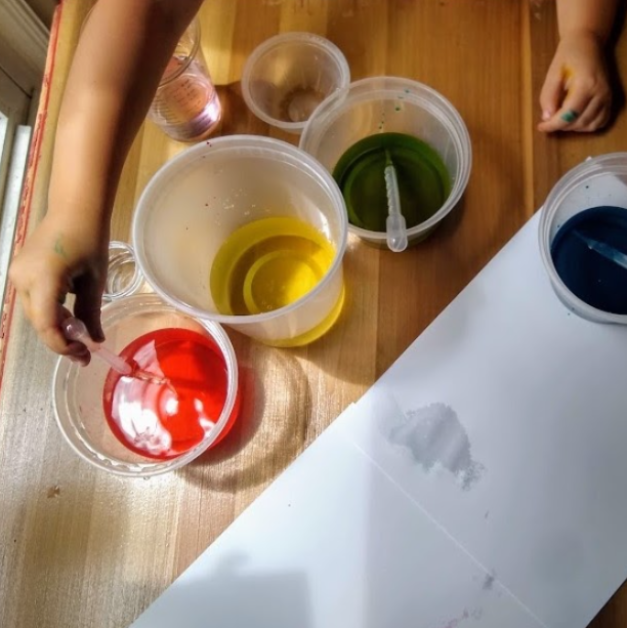

We know, though, that words are not quite enough. For things like play and creativity, one needs an embodied experience. So, student teachers were given empty cups, primary colors (red, yellow, and blue) in both tempera paint and watercolor and no instructions beyond “mix your favorite color.” Some students knew right away how to make their favorite color. Others had to experiment or ask around for advice. They quickly saw and felt the difference in the different kinds of paint, some of which was thick and easy to mix, some of which was not. As they mixed, they shared details from their lives- pets, children, hobbies. In short, through playing with materials, they formed relationships to the materials and each other just like what we hoped children would do when the school year started.

Wonder School student teachers sit together in the Wonder School “back yard” to mix paint during orientation week.

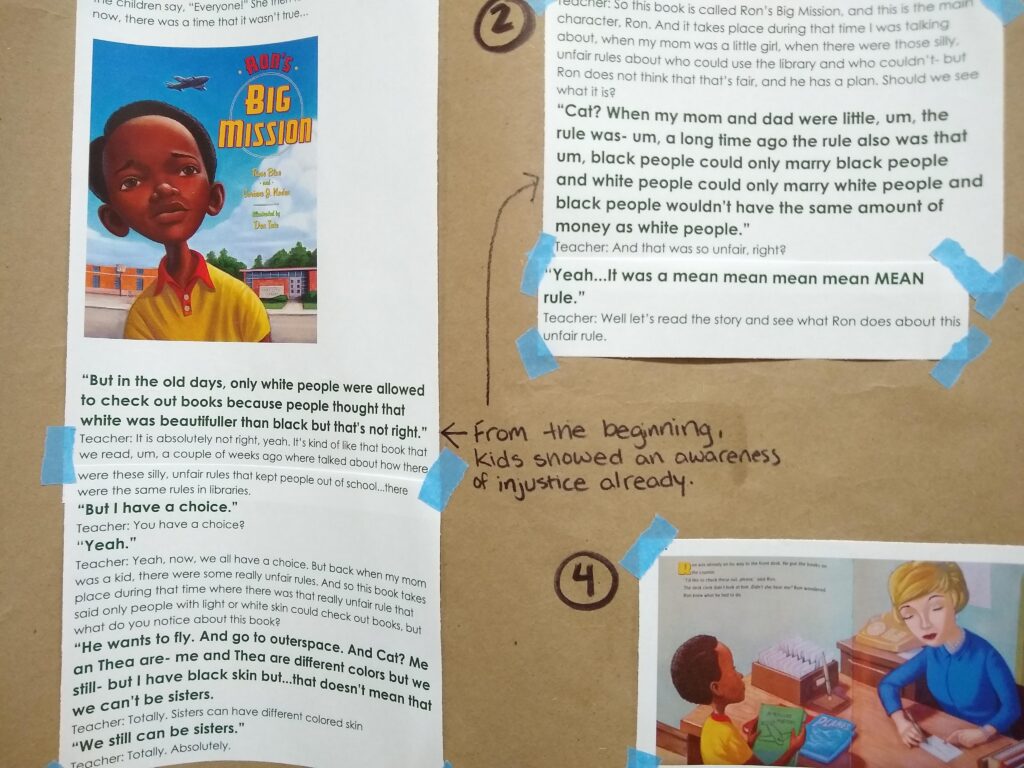

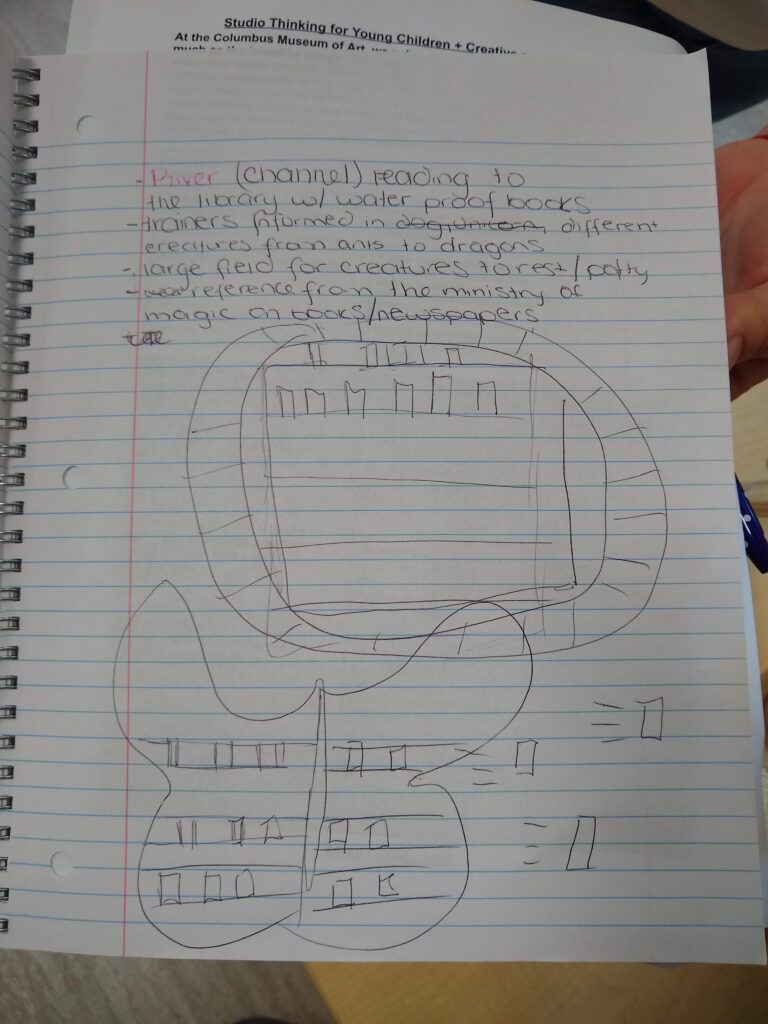

Next, we had them do a creativity challenge. At CMA, “creativity challenges” are short, usually one-sentence prompts inviting imaginative action, often playful or containing unexpected juxtapositions (e.g. Design a feast for dragons). Creativity challenges are usually meant to be completed quickly, around 5 or 10 minutes. They are meant to be quick, non-precious and spark very specific types of ‘thinking’ that can sometimes get lost in longer or more serious-feeling art projects. For this particular challenge, we wanted to gently nudge the student teachers to think about how creativity relates to the civic dimension by thinking about some of the tricky things that can come up when trying to design shared space. First, the student teachers were asked to think about what they know about libraries, then to generate a list of animals and fictional characters. Next, the student teachers were tasked with making a library that would meet the needs of all these creatures and characters. As students worked, CMA teaching artists made sure to have the group share mid-process and to then intentionally ‘steal’ some aspect of someone else’s design. Finally, the students were asked to share not just what they did, but also how their idea shifted by hearing their classmates’ ideas.

Student teachers were invited to use either a paper and pen or 3D building materials to imagine their new libraries.

During the reflection, student teachers shared that “it was fun to have other (people’s) ideas to bounce off of,” and that they, “liked having the chance to have my own ideas…but I’ve learned (my ideas) aren’t always the best ideas.” When asked about the emotional experience of the creativity challenge, students reported feeling “more opened up,” “expanded,” and that the experience was “weird but fun.” One student reflected that, “as we grow older we lose that sense of having that imagination we used to have… We forget that we can go back.”

Wonder, play, and listening carefully are essential in our Wonder School classroom. Asking the student teachers to practice these skills with each other sets them up to be better able to model them with children, both in their formal activity plans and in the small moments that make up daily life in a classroom.

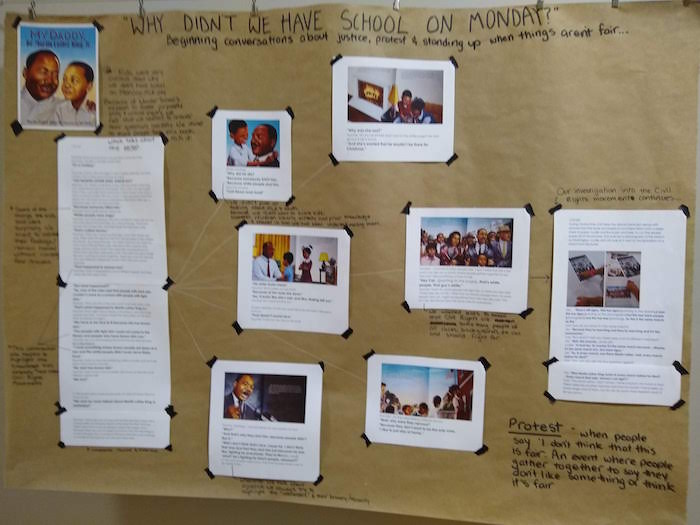

“Big kids” and “little kids” supporting one another in moments of creativity.

“Big kids” and “little kids” supporting one another in moments of creativity.

– Caitlyn Lynch is CMA Lead Teaching Artist & Coordinator for Young Child Programming including Wonder School, an arts-rich laboratory preschool launched in 2018 in collaboration with Columbus State Community College, Columbus Museum of Art, and The Childhood League Center. Wonder School fosters purposeful play, critical inquiry, and a collaborative community approach to education—for children, for their educators, for a more creative and compassionate society.